Saturday, November 29, 2014

Urban Artists, Navajo Nation

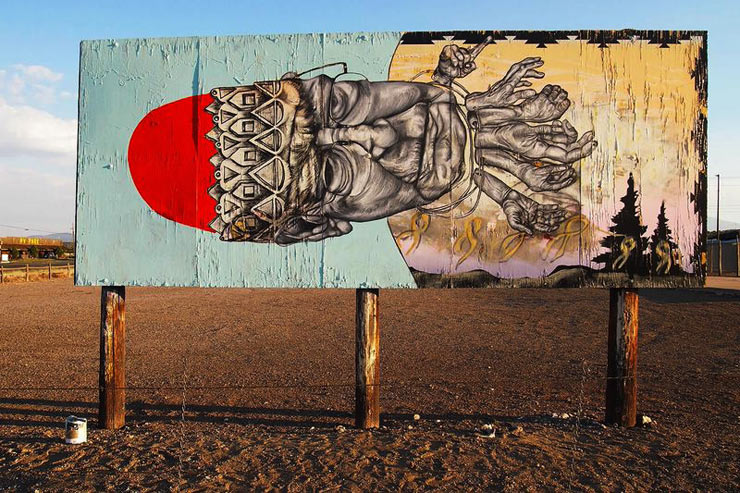

"In the third year of his experiment inviting artists to paint and wheat-paste in the Navajo Nation, organizer Chip Thomas, whose own street persona is Jetsonorama, appears to have hit a community service vein. “The relationship with the community became deeper,” he says as he relates the integration of some of the artists work relating directly to the history and the stories people tell in this sunbaked part of Arizona. More residency than festival, “The Painted Desert Project” began as a retreat offered to artists Thomas had met through his own association with Street Art festivals like Open Walls in Baltimore."

read and see more here

Thursday, November 27, 2014

Tuesday, November 25, 2014

Gifted Anomaly - Worship

Friday, November 21, 2014

Questlove interviews Cornel West

QUESTLOVE: So you were teaching your class about the difference in

social impact between Marcus Garvey and Du Bois. And what I took away

was the question of whether we need a messiah figure to lead society, or

can it be truly grassroots? I also wonder what good it will do today.

Chuck D taught me a long time ago to aim really small. And everyone now

has [Michael] Jordan-itis—everyone wants the star position. So where do

you fall, on the question of how we can best move forward as a society,

between the Moses-messiah figure, like Martin Luther King Jr. or, say,

Occupy Wall Street, which really didn't have a leader?

CORNEL WEST: I take my fundamental cue from John Coltrane that says there must be a priority of integrity, honesty, decency, and mastery of craft. I take my second cue from [organizer and activist] Ella Baker that says, with that integrity, honesty, decency, master of craft, there must be an attempt to find, among everyday people, vision, voice, and modes of organizing and mobilizing that does not result in the messianic model, in the HNIC, the head negro in charge. This is where Martin King comes in, and the distinction we made in class between conspicuous charisma and service-oriented charisma. It's possible to be highly charismatic the way John Coltrane was, and still de-center oneself, as he did, to allow for McCoy, and Elvin, and Reggie, and the others [who played with Coltrane] to lift their voices with tremendous power. Martin, at his best, was able to empower others, galvanize others and, through an integrity and humility, recognize he's just another human being, not a messiah. At his worst, he was the Moses that everybody had to defer to.

read the rest here

CORNEL WEST: I take my fundamental cue from John Coltrane that says there must be a priority of integrity, honesty, decency, and mastery of craft. I take my second cue from [organizer and activist] Ella Baker that says, with that integrity, honesty, decency, master of craft, there must be an attempt to find, among everyday people, vision, voice, and modes of organizing and mobilizing that does not result in the messianic model, in the HNIC, the head negro in charge. This is where Martin King comes in, and the distinction we made in class between conspicuous charisma and service-oriented charisma. It's possible to be highly charismatic the way John Coltrane was, and still de-center oneself, as he did, to allow for McCoy, and Elvin, and Reggie, and the others [who played with Coltrane] to lift their voices with tremendous power. Martin, at his best, was able to empower others, galvanize others and, through an integrity and humility, recognize he's just another human being, not a messiah. At his worst, he was the Moses that everybody had to defer to.

read the rest here

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

Monday, November 17, 2014

DJ Fly - 2013 DMC World Champion

Also the 2008 Champion:

Sunday, November 16, 2014

What Hip-Hop Can Teach Academia

"The hip-hop world has a lot more

in common with academia than most people think -- and it has important lessons

for the endless academic hand-wringing over its public relevance. Beat-making

and hip-hop lyrics are essentially a dense web of footnotes and citation. It is

as literally impossible for the novice to understand the meaning of the

complex, highly local references to Brooklyn personalities, hip-hop history,

and gangster culture in a Jay-Z verse as it is for the uninitiated to make

sense of a sophisticated theoretical text. Unlike academia, however, hip-hop

adapted a long time ago to the recording industry's Internet-fueled crisis --

and came out stronger for its struggles.

For those who don't follow such things, Kendrick Lamar is a young rapper from Compton, California who took the music world by the throat last year. Last year, he released one of the best albums of the last decade, Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City, which received rapturously thoughtful reviews and went platinum (even when the album leaked, you see, fans still bought it for proof). He turned in star guest verses for contemporaries like A$AP Rocky, B.o.B, and Pusha T to rap gods like Eminem and Talib Kweli. He opened for Kanye West's Yeezus tour. He appeared on about a million magazine covers, and received seven Grammy nominations.

And then he lost them all -- to Macklemore. ('Nuff said.) Everyone, including Macklemore, understood that this was as close to a crime against humanity as the Grammys allow. But instead of sulking, whining, or grabbing the mic from Taylor Swift, Kendrick used his scheduled Grammy performance to make Imagine Dragons, one of the year's top-selling rock bands, into his backup band and, well, let Kendrick tell it: "I need you to recognize that Plan B is to win your hearts right here while we're at the Grammys." And he did, with a triumphant, uncompromising performance that brought down the house and momentarily made the Grammys matter again. Instead of brooding over the ignorance of the gatekeepers, Kendrick just seized the moment and went out and relegated them to irrelevance.

That's what academic bloggers have been doing for the last decade: ignoring hierarchies and traditional venues and instead hustling on our own terms. Instead of lamenting over the absence of an outlet for academics to publish high-quality work, we wrote blogs on the things we cared about and created venues like the Middle East Channel and the Monkey Cage. Academic blogs and new primarily online publications rapidly evolved into a dense, noisy, and highly competitive ecosystem where established scholars, rising young stars, and diverse voices battled and collaborated."

Read here: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2014/02/03/what_hip_hop_and_kendrick_lamar_can_teach_academia

For those who don't follow such things, Kendrick Lamar is a young rapper from Compton, California who took the music world by the throat last year. Last year, he released one of the best albums of the last decade, Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City, which received rapturously thoughtful reviews and went platinum (even when the album leaked, you see, fans still bought it for proof). He turned in star guest verses for contemporaries like A$AP Rocky, B.o.B, and Pusha T to rap gods like Eminem and Talib Kweli. He opened for Kanye West's Yeezus tour. He appeared on about a million magazine covers, and received seven Grammy nominations.

And then he lost them all -- to Macklemore. ('Nuff said.) Everyone, including Macklemore, understood that this was as close to a crime against humanity as the Grammys allow. But instead of sulking, whining, or grabbing the mic from Taylor Swift, Kendrick used his scheduled Grammy performance to make Imagine Dragons, one of the year's top-selling rock bands, into his backup band and, well, let Kendrick tell it: "I need you to recognize that Plan B is to win your hearts right here while we're at the Grammys." And he did, with a triumphant, uncompromising performance that brought down the house and momentarily made the Grammys matter again. Instead of brooding over the ignorance of the gatekeepers, Kendrick just seized the moment and went out and relegated them to irrelevance.

That's what academic bloggers have been doing for the last decade: ignoring hierarchies and traditional venues and instead hustling on our own terms. Instead of lamenting over the absence of an outlet for academics to publish high-quality work, we wrote blogs on the things we cared about and created venues like the Middle East Channel and the Monkey Cage. Academic blogs and new primarily online publications rapidly evolved into a dense, noisy, and highly competitive ecosystem where established scholars, rising young stars, and diverse voices battled and collaborated."

Read here: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2014/02/03/what_hip_hop_and_kendrick_lamar_can_teach_academia

Green's History of Slang

Not directly related to hip-hop but the topic of 'slang' is certainly relevant:

"America’s greater tolerance for the genius inherent in

grassroots language may well explain why its literature, from Mark Twain

to Philip Roth, is better connected to the “workingman” as a speaking

subject rather than as an object of anxiety. In the 21st-century world,

where informal oral media (TV, film, YouTube) shape global discourse, it

is American slang that has “gone the distance.”

Green offers us 18 broadly chronological chapters on the

history of slang. Some of these chapters focus on particular forms where

slang is to be found (e.g., “The Stage and the Song”), others on

particular speech communities (Australia, America, African Americans),

others on recurrent themes (sex, sports, war). There is much here of

interest, yet it must be confessed that the material is sometimes drier

than such a lubricious subject would lead one to anticipate. Green has

elsewhere written explicitly for the popular market: He is responsible

for such tomes as The Big Book of Filth (1999), The Big Book of Bodily Functions (2001), and the Dictionary of Insulting Quotations (1997).

Here, however, he is writing as a lexicographer for an academic press,

and some of these chapters make dense reading for anyone who does not

have a scholarly interest in the development of vernacular language.

Green’s method is to cite sources (authors, books) rich in recorded

slang and to discuss their place in the development of the glossary of

what we know (or assume) to have been slang patter across the years.

These sources can involve fascinating micro-narratives, as when we are

introduced to characters such as John Taylor (1578-1653), the

“Water-Poet,” a writer who had made his living as a boatman and traded

on this to make a literary splash. Long before the days of Amazon, he

became a successful pioneer of self-publishing, largely through

publicity stunts designed to attract readers’ interest. He would plan a

journey—to Prague, or on foot from London to Edinburgh with no money—and

then seek sponsorship to undertake the trip and write about it. He

produced at least 150 works, liberally larded with loose language."

Thursday, November 13, 2014

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

R.I.P. Big Bank Hank (from the Sugerhill Gang)

"TMZ reports

that Big Bank Hank, one third of pioneering rap group the Sugarhill

Gang, died early this morning after a battle with cancer. Hank, born

Henry Jackson, was 57.

The Sugarhill Gang, and Hank in particular, have a long and strange story. Hip-hop had been thriving as live party music in the Bronx for years before the group recorded 1979′s “Rapper’s Delight,” the first-ever hit hip-hop record, in 1979. The Sugarhill Gang weren’t really a part of that scene. Instead, Sugarhill Records founder Sylvia Robinson put the group together. Legend has it that she had the idea after hearing Hank rap while he was serving her pizza in a New Jersey restaurant."

read rest here

The Sugarhill Gang, and Hank in particular, have a long and strange story. Hip-hop had been thriving as live party music in the Bronx for years before the group recorded 1979′s “Rapper’s Delight,” the first-ever hit hip-hop record, in 1979. The Sugarhill Gang weren’t really a part of that scene. Instead, Sugarhill Records founder Sylvia Robinson put the group together. Legend has it that she had the idea after hearing Hank rap while he was serving her pizza in a New Jersey restaurant."

read rest here

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

"Hip Hop's Promising New Role in Therapy"

"A growing body of research suggests that those who live in

violence-stricken communities are subject to post-traumatic stress and PTSD at rates higher than the rest of the country.

One creative antidote to this unfortunate reality may be found, perhaps not surprisingly, in the music that emerged alongside the culture of the inner city: hip hop.

Cendrine Robinson, a clinical psychology student at Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, recently published an article, "Dream & nightmares: What hip-hop can teach us about Black youth," in American Psychological Association's newsletter, In the Public Interest. In her article, Robinson discusses her experience using hip hop to counsel at-risk youth.

From counseling teenage girls about HIV prevention, to helping young men on probation and Iraq war veterans, Robinson said that the inclusion of hip hop music helps to start a dialogue between client and therapist through a vocabulary and framework comfortable for both.

Robinson writes, "Hip hop therapy has elements of expressive therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. Hip hop music is utilized to engage clients in treatment by helping establish rapport with the therapist. Music can also help clients identify emotions and reframe cognition."

Artists like Chief Keef, Meek Mill and Rick Ross now populate Robinson's Pandora stations, because they are the artists the majority of her clients are listening to. She has found Meek Mill particularly helpful in this respect, especially his song "Traumatized."

In an interview with The Fader, Meek Mill said about Robinson's research, "That's what I make the music for, to be able to touch people. Even if you didn't come from the hood. You don't have to be from the streets."

As Robinson says in her article, "If we listen carefully, we may be able to find better solutions to address the pervasive violence in our community."

read the rest here

One creative antidote to this unfortunate reality may be found, perhaps not surprisingly, in the music that emerged alongside the culture of the inner city: hip hop.

Cendrine Robinson, a clinical psychology student at Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, recently published an article, "Dream & nightmares: What hip-hop can teach us about Black youth," in American Psychological Association's newsletter, In the Public Interest. In her article, Robinson discusses her experience using hip hop to counsel at-risk youth.

From counseling teenage girls about HIV prevention, to helping young men on probation and Iraq war veterans, Robinson said that the inclusion of hip hop music helps to start a dialogue between client and therapist through a vocabulary and framework comfortable for both.

Robinson writes, "Hip hop therapy has elements of expressive therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. Hip hop music is utilized to engage clients in treatment by helping establish rapport with the therapist. Music can also help clients identify emotions and reframe cognition."

Artists like Chief Keef, Meek Mill and Rick Ross now populate Robinson's Pandora stations, because they are the artists the majority of her clients are listening to. She has found Meek Mill particularly helpful in this respect, especially his song "Traumatized."

In an interview with The Fader, Meek Mill said about Robinson's research, "That's what I make the music for, to be able to touch people. Even if you didn't come from the hood. You don't have to be from the streets."

As Robinson says in her article, "If we listen carefully, we may be able to find better solutions to address the pervasive violence in our community."

read the rest here

2013 - 불한당가 (Korea)

不 汗 黨 歌

no sweat crew/party anthem

Monday, November 10, 2014

Hip-Hop and Religion

read original article here by: Kwanele Sosibo

I had these thoughts dancing in my mind when I visited an old acquaintance in a Craighall complex the other day. I remembered once, almost ten years ago, riding wild in the streets of Joburg trying to decipher his copy of Ghostface Killah’s woozy classic Supreme Clientele. Ghostface, a proclaimed adherent of the Five Percent Nation’s beliefs (they believe that Allah is the physical black man – Arm, Leg, Leg, Arm, Head), took language to extreme heights by melding the “supreme alphabet” (a coded language based on ascribing meaning to each letter of the alphabet) to his already heady, psychedelic street poems. That album pretty much cemented his place as one of the culture’s premier lyricists, even though much of his subject matter tread worn ground.

Today, Mfundisi Dlungu is a self-employed architect. When we do reminisce about hip-hop’s importance, it is with the distance and objectivity of hindsight, and arguments about who is the “freshest” are underscored by an existential urgency.

Seated on opposite ends of a work desk in his lounge, Dlungu – an athletic figure in a pale yellow shirt, cream jeans and white cross-trainers – cues tracks on his iPad as we chew the fat on our favourite subject. “What made me check for it [hip-hop] was that they were saying that Islam was a religion for the black man, and not Christianity,” says Dlungu. Emerging from the kitchen, he places drinks on wooden coasters and continues. “But when I checked both of these religions, neither belonged to us. So how could we, as Africans, lay claim to something that is not ours?”

Dlungu, a “Christian by default” who never goes to church, adds that it was the mixed messages that led him to doubt hip-hop as a catalyst to spiritual awakening. “Even these cats who were representing that Five Percent thing, they were still about drinking 40 ounces [a measure of beer]. How are you gonna be a Muslim if you’re drinking and fucking whores?” he asks rhetorically. “There wasn’t consistency in what they were saying. In terms of spirituality, the only thing I found in hip-hop was “keeping it real”. Do you! That was the only thing more than the religious part of it because that was a mess…”

Today, the idea of keeping it real is something of a laughing stock in hip-hop. It is an antiquated concept based on keeping your subject matter congruous with your daily reality. Nevertheless, it did bestow on Dlungu a strong template for forming his own identity. Today, he still speaks in “golden era” hip-hop slang laced with expletives but without the requisite accent as he dissects the culture’s sinister materialism. “Who can relate to holding money and just throwing it out there, unless you are a stupid motherfucker,” he says in reference to a standard image in mainstream hip-hop videos. “Even if I was to make my money I still couldn’t relate to that. You can relate to Shaq saying ‘my biological didn’t bother’. It just inspired me to be an individual.”

For a while, during our adolescence in the nineties, it felt like hip-hop could answer all of life’s questions for us. While it evolved spontaneously, it was nurtured by healthy doses of street corner intellect and convergent esoterica to such an extent that relating to hip-hop has often felt like relating to an all-knowing, all-powerful being.“You are dealing with heaven, while you are walking through hell. When I say heaven, I don’t mean up in the clouds, because heaven is no higher than your head and hell is no lower than your feet.”–Rakim, as told to journalist Harry Allen.

I had these thoughts dancing in my mind when I visited an old acquaintance in a Craighall complex the other day. I remembered once, almost ten years ago, riding wild in the streets of Joburg trying to decipher his copy of Ghostface Killah’s woozy classic Supreme Clientele. Ghostface, a proclaimed adherent of the Five Percent Nation’s beliefs (they believe that Allah is the physical black man – Arm, Leg, Leg, Arm, Head), took language to extreme heights by melding the “supreme alphabet” (a coded language based on ascribing meaning to each letter of the alphabet) to his already heady, psychedelic street poems. That album pretty much cemented his place as one of the culture’s premier lyricists, even though much of his subject matter tread worn ground.

Today, Mfundisi Dlungu is a self-employed architect. When we do reminisce about hip-hop’s importance, it is with the distance and objectivity of hindsight, and arguments about who is the “freshest” are underscored by an existential urgency.

Seated on opposite ends of a work desk in his lounge, Dlungu – an athletic figure in a pale yellow shirt, cream jeans and white cross-trainers – cues tracks on his iPad as we chew the fat on our favourite subject. “What made me check for it [hip-hop] was that they were saying that Islam was a religion for the black man, and not Christianity,” says Dlungu. Emerging from the kitchen, he places drinks on wooden coasters and continues. “But when I checked both of these religions, neither belonged to us. So how could we, as Africans, lay claim to something that is not ours?”

Dlungu, a “Christian by default” who never goes to church, adds that it was the mixed messages that led him to doubt hip-hop as a catalyst to spiritual awakening. “Even these cats who were representing that Five Percent thing, they were still about drinking 40 ounces [a measure of beer]. How are you gonna be a Muslim if you’re drinking and fucking whores?” he asks rhetorically. “There wasn’t consistency in what they were saying. In terms of spirituality, the only thing I found in hip-hop was “keeping it real”. Do you! That was the only thing more than the religious part of it because that was a mess…”

Today, the idea of keeping it real is something of a laughing stock in hip-hop. It is an antiquated concept based on keeping your subject matter congruous with your daily reality. Nevertheless, it did bestow on Dlungu a strong template for forming his own identity. Today, he still speaks in “golden era” hip-hop slang laced with expletives but without the requisite accent as he dissects the culture’s sinister materialism. “Who can relate to holding money and just throwing it out there, unless you are a stupid motherfucker,” he says in reference to a standard image in mainstream hip-hop videos. “Even if I was to make my money I still couldn’t relate to that. You can relate to Shaq saying ‘my biological didn’t bother’. It just inspired me to be an individual.”

Sunday, November 9, 2014

Saturday, November 8, 2014

Friday, November 7, 2014

San E - Rap Circus (Korea)

A friend pointed out:

Thursday, November 6, 2014

2011 MC Meta - 사투리의 눈물 & 무까끼하이 (Korea)

Rapping in a southern Korean dialect as opposed to "proper" Korean or "Seoul Speech/Talk," which makes this piece particular - especially in an age when local dialects are not being used as often as they used to be (some Korean scholars have projected the eventual extinction of local dialects because of a bias against them in the Seoul job market and the association that they are too "country" or "unintelligent"; students (from elementary to high school and college) have experienced discrimination as well; for those who understand Korean - sorry no subs - click here: '사투리의 눈물'

which is a documentary that discusses this issue; it's good, the soundtrack is above)

Wednesday, November 5, 2014

Monday, November 3, 2014

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)